Other Discoveries from Carrington's Flare: Difference between revisions

imported>Wikisysop |

imported>Hhudson (tidying-up, adding links to Balfour Stewart etc) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

This is the [http://www.astro.gla.ac.uk/%7Eiain/flares150/ sesquicentennial] of Richard Carrington's solar flare of 1859. | This is the [http://www.astro.gla.ac.uk/%7Eiain/flares150/ sesquicentennial] of Richard Carrington's solar flare of 1859. | ||

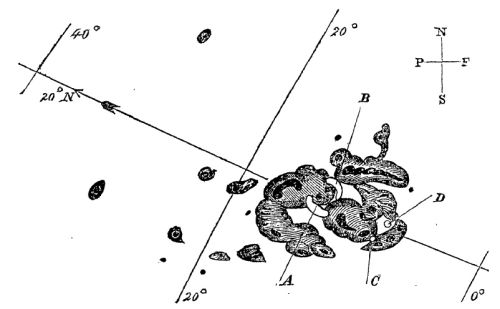

He saw it in "white light" as he was measuring sunspots, and the sketch he made (Figure 1) is often displayed. | He saw it in "white light" (ordinary visible continuum) as he was measuring sunspots, and the sketch he made (Figure 1) is often displayed. | ||

The idea that small parts of the very bright solar atmosphere could ''double'' in intensity in a such a short time must have astonished the observers | The idea that small parts of the very bright solar atmosphere could ''double'' in intensity in a such a short time must have astonished the observers: not only Carrington himself but also his assistant, plus an entirely independent observer named Richard Hodgson. | ||

Detailed research has shown that this latter observer was not a weakish speller who might have been related to the Nugget | Detailed research has shown that this latter observer was not a weakish speller who might have been related to the author of this RHESSI Science Nugget. | ||

In Figure 1, the state of the art | In Figure 1, at the state of the art of scientific graphics in 1859, the letters A, B, C, and D point to the flare brightenings. | ||

The spot umbrae and penumbrae appear somewhat stylized, but Carrington was notoriously correct in his observational work and analyses of it. | |||

This Nugget is not about the flare in (or near) the photosphere itself, but about its effects on Earth. | This Nugget is not about the flare in (or near) the photosphere itself, but about its effects on Earth. | ||

It was not really Carrington's work (see below) but he nevertheless thought it important to report the association between the flare and its terrestrial effects. | |||

It was in fact a phenomenally important | It was in fact a phenomenally important association, which he famously described in the best British style of understatement as "One swallow does not make a summer." | ||

[[Image:carrington.jpg|500px|thumb|center|'''Figure 1''': The Carrington white-light sketch. The emissions were very bright, of a color resembling Alpha Lyrae, and rapidly variable ("mortifying" in his description). These properties have been confirmed by subsequent observations.]] | [[Image:carrington.jpg|500px|thumb|center|'''Figure 1''': The Carrington white-light sketch. The emissions were very bright, of a color resembling Alpha Lyrae, and rapidly variable ("mortifying" in his description). These properties have been confirmed by subsequent observations of similar events.]] | ||

==The other 1859 observation== | ==The other 1859 observation== | ||

When the flare happened, the recording | When the flare happened, the recording magnetograph at [http://books.google.com/books?id=K6cOAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA37 Kew Gardens observatory] was in operation. | ||

It was known that a sensitive compass (magnetometer) could see all manner of variations at a low level. | It was known that a sensitive compass (magnetometer) could see all manner of variations at a low level. | ||

In fact, [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Balfour_Stewart Balfour Stewart], the director at Kew Observatory, independently noted many flare-induced disturbances during the disk passage of the sunspot group responsible for the Carrington flare (about two weeks). | |||

The polymath [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Friedrich_Gauss Gauss] had already established that these variations were external perturbations of the geomagnetic field, which in the bulk had its origins (we know now) deep in the iron-nickel core of the Earth. | The polymath [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Friedrich_Gauss Gauss] had already established that these variations were external perturbations of the geomagnetic field, which in the bulk had its origins (we know now) deep in the iron-nickel core of the Earth. | ||

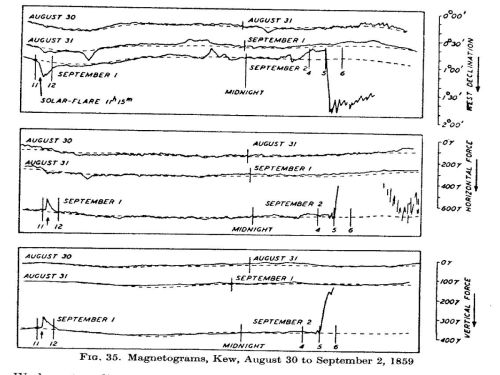

The Carrington flare now strongly suggested that some of these variations could ultimately be traced to the Sun, rather than to near-Earth space, and the Kew observation shown below (Figure 2) shows that these could be prompt. | The Carrington flare now strongly suggested that some of these variations could ultimately be traced to the Sun, rather than to near-Earth space, and the Kew observation shown below (Figure 2) shows that these could be prompt. | ||

| Line 43: | Line 45: | ||

The plasma moves one [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Astronomical_unit A.U.] in about 17 hours. | The plasma moves one [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Astronomical_unit A.U.] in about 17 hours. | ||

This means a speed of some 2500 km/s, which would be near the high end of speeds of solar ejecta as befits such a powerful flare event. | This means a speed of some 2500 km/s, which would be near the high end of speeds of solar ejecta as befits such a powerful flare event. | ||

The compass deflections during the main magnetic storm | The compass deflections during the main magnetic storm result from other current systems, driven not by the regular diurnal effects of the steady solar wind, but by the stresses of the CME itself. | ||

==Conclusion== | ==Conclusion== | ||

Revision as of 02:59, 3 February 2009

| Nugget | |

|---|---|

| Number: | 94 |

| 1st Author: | Hugh Hudson |

| 2nd Author: | |

| Published: | 2 February 2009 |

| Next Nugget: | TBD |

| Previous Nugget: | Collapsing_traps |

Introduction

This is the sesquicentennial of Richard Carrington's solar flare of 1859. He saw it in "white light" (ordinary visible continuum) as he was measuring sunspots, and the sketch he made (Figure 1) is often displayed. The idea that small parts of the very bright solar atmosphere could double in intensity in a such a short time must have astonished the observers: not only Carrington himself but also his assistant, plus an entirely independent observer named Richard Hodgson. Detailed research has shown that this latter observer was not a weakish speller who might have been related to the author of this RHESSI Science Nugget. In Figure 1, at the state of the art of scientific graphics in 1859, the letters A, B, C, and D point to the flare brightenings. The spot umbrae and penumbrae appear somewhat stylized, but Carrington was notoriously correct in his observational work and analyses of it.

This Nugget is not about the flare in (or near) the photosphere itself, but about its effects on Earth. It was not really Carrington's work (see below) but he nevertheless thought it important to report the association between the flare and its terrestrial effects. It was in fact a phenomenally important association, which he famously described in the best British style of understatement as "One swallow does not make a summer."

The other 1859 observation

When the flare happened, the recording magnetograph at Kew Gardens observatory was in operation. It was known that a sensitive compass (magnetometer) could see all manner of variations at a low level. In fact, Balfour Stewart, the director at Kew Observatory, independently noted many flare-induced disturbances during the disk passage of the sunspot group responsible for the Carrington flare (about two weeks). The polymath Gauss had already established that these variations were external perturbations of the geomagnetic field, which in the bulk had its origins (we know now) deep in the iron-nickel core of the Earth. The Carrington flare now strongly suggested that some of these variations could ultimately be traced to the Sun, rather than to near-Earth space, and the Kew observation shown below (Figure 2) shows that these could be prompt. It was correctly argued by Kelvin that these perturbations could not result directly from changes of solar magnetism, but nobody at the time had the imagination to anticipate X rays or the ionosphere, both key ingredients to an explanation of Figure 2.

One of the main purposes of this Nugget is just to circulate Figure 2, which is not as well-known as Carrington's sketch. However it contains a lot of discovery. We now know there is an ionosphere. Solar soft X-radiation increases the ionization level, and naturally occurring EMF's drive enhanced currents, which in turn deflect compass needles. This is an example of a Sudden Ionospheric Disturbance, or SID. There are many other different ionospheric effects resulting from different solar emissions and ionospheric properties, and prior to the era of space research these ionospheric effects provided many clues to flare physics.

This is the beginning of "space weather". The initial compass perturbation is due to photons, traveling at the speed of light. The later magnetic storm is due to solar plasma ejected by the flare (a Coronal Mass Ejection). The plasma moves one A.U. in about 17 hours. This means a speed of some 2500 km/s, which would be near the high end of speeds of solar ejecta as befits such a powerful flare event. The compass deflections during the main magnetic storm result from other current systems, driven not by the regular diurnal effects of the steady solar wind, but by the stresses of the CME itself.

Conclusion

The white-light flare phenomenon, of which Carrington's 1859 event was the first recorded, is something that RHESSI can study important aspects of, namely the hard X-ray emission that we have discussed in earlier Nuggets (11, 76, 92). There are still mysteries associated with these powerful phenomena, possibly involving gamma-rays from pion decay, sunquakes, or other exotica. Probably the ionosphere is too crude a detector to be of much use any longer, but we should not forget its great contributions over the fifteen decades since Carrington's time!