Flare Observed by a Dozen Instruments

| Nugget | |

|---|---|

| Number: | 231 |

| 1st Author: | Lucia Kleint |

| 2nd Author: | Kevin Reardon |

| Published: | July 28, 2014 |

| Next Nugget: | TBD |

| Previous Nugget: | RHESSI is Annealing Now |

Introduction

We live in a golden age for research on solar flares, observationally speaking. This statement reflects not only the existence of powerful satellite observatories (RHESSI, Hinode, SDO, Fermi, STEREO, and now IRIS, as well as basic standbys such as GOES), but also advanced ground-based instrumentation at observatories such as the powerful Arcetri/NSO IBIS instrument. limited of course by observatory longitudes and the resulting day/night problem. In addition many spacecraft also observe the interplanetary consequences of a solar eruption. Count the instruments up and one quickly exceeds a dozen; these instruments individually mostly have unique capabilities and people cheerfully write papers about their particular individual discoveries. Put them all together and one has a wonderful opportunity to gain a broad insight into flare development, if fortune smiles and many actually have suitable coverage.

Just about that situation happened on March 29, 2014, when SOL2014-03-29 (X1.0) occurred; see the SDO movies.

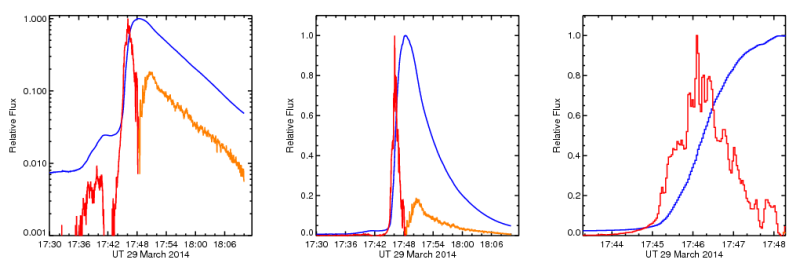

All of the observatories listed above got some data, mostly with good coverage and with correct pointing. A high-resolution observatory can often miss a big flare simply by staring at the wrong spot. For general reference we offer Figure 1, showing the basic GOES time history.

What's really new: IBIS

The Interferometric Bidirectional Imaging Spectropolarimeter (IBIS) is one of several excellent ground-based instruments in the field now. The name describes the instrument pretty well. Figure 2 shows some of its fortunate observations of SOL2014-03-29, for which the slit had an excellent positioning.

IBIS scanned photospheric and chromospheric spectral lines, giving us information about the intensities, velocities, and magnetic fields in these layers. It probably is the first time that an X-flare was observed with such high spatial resolution (0.2 arcsec), and with chromospheric polarimetry.

What's really new: IRIS

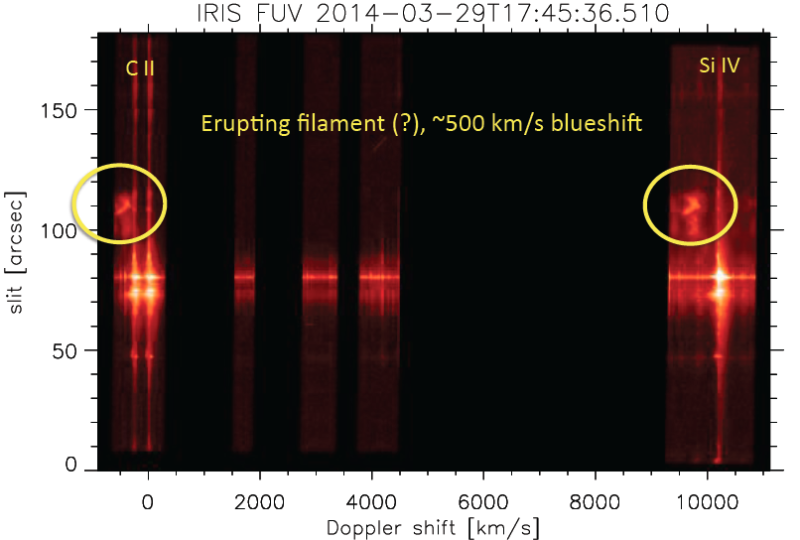

The newest participant is the IRIS spacecraft, the first really to target the "interface region" bridging the gap between the hot surface of the Sun (the photosphere) and the very hot corona. Figure 3 shows one slice of data from this instrument, which essentially records four-dimensional "data cubes" (two spatial coordinates, time, and spectrum). The figure shows one dimension of the full 2D imaging, which requires the scanning of its long slit; at each position it shows a high-resolution spectrum.

It is confusing that IBIS and IRIS have such similar acronyms!

Conclusions

It often happens that a major flare happens and everybody in the community scrambles to write a "gee whiz" paper about the particularly noteworthy thing their instrument has seen. Often, of course, they include as much data from other sources as possible, and of course they work hard at drawing physically meaningful conclusions. Nevertheless they tend to work simultaneously and not necessarily in a coordinated way, and what appears in the literature may be disorganized as a result. In view of the breadth of coverage for this very nice event, many research workers will be studying it.

Only seldom does the community do a retrospective look at a given well-observed event, but we recommend that here because of the excellent coverage.

We also suggest contacting the authors of this Nugget for help in joint analyses if desired.