A Solar FRB

| Nugget | |

|---|---|

| Number: | 400 |

| 1st Author: | Dale GARY |

| 2nd Author: | Hugh HUDSON |

| Published: | 15 February 2021 |

| Next Nugget: | TBD |

| Previous Nugget: | Richard Schwartz |

Introduction

The idea of a "Fast Radio Burst" (FRB) burst upon the astronomical community only 15 years ago: these are remarkbly bright, remarkably fast transient sources. They last for only a few msec! Most of them, quite interestingly, have extragalactic origins, as can be inferred from their frequency dispersion, typically hundreds of pc/cm3. Here the unit pc is the parsec. Many may be associated with magnetars, which links them to both RHESSI and to solar flares.

Recently a very sensitive FRB detector array detected a FRB-like event, but uniquely solar in origin (Ref. [1]). We'll call it the SFRB, for "solar FRB". This event, observed at 1.6 GHz, lasted for only a few ms and thus seemed like a true FRB. Here the dispersion measure, still expressed in parsecs, was a minimal 5 pc/cm3, but consistent with zero (or the whole solar corona, which has a scale height of about 1 nanoparsec. Figure 1 shows the STARE2 array detection by two instruments at the Owens Valley Radio Observatory.

The solar event

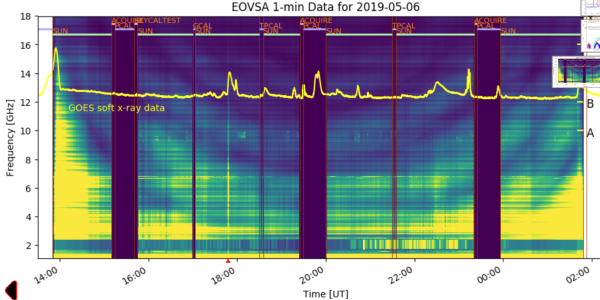

Our new solar radio observatory, EOVSA, also at Owens Valley, detected something remarkable at about the right time: Figure 2 shows the file EOVSA spectrogram, with a fast broadband

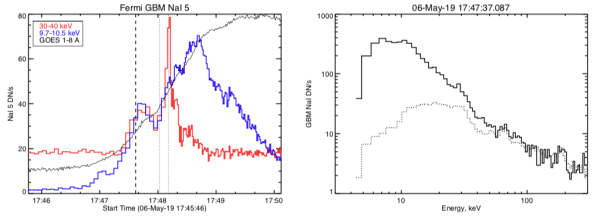

RHESSI hard X-ray data were not available when this event happened, but [Fermi/GBM] data were, as shown in Figure 3 here. During the SFRB there was hard X-ray emission with extremely hard spectra (index about -2.8), but no coincident spike. The EOVSA data show that the disturbance penetrated to the lower solar atmosphere, and so this non-coincidence likely just results from the relatively poor time resolution of the GRB data, 4 s rather than 4 ms.

The EOVSA data provide the best possible solar radio observational material, which we summarize in Figure 4 here. EOVSA's high time resolution (20 ms samples) still do not resolve the time scale of the STARE2 event (Figure 1), and are achieved by time-sharing, rather than continuous sampling. In this case EOVSA scans were at either 8.25-8.55 GHz or 10.2-10.5 GHz, in any case at much higher frequencies than the 1.6 GHz of the STARE2 detection.

The morphology of the spectrogram in Figure 4 resembles that of type III bursts, normally observed in the corona at much lower frequencies. Here we are seeing source densities, on the plasma-frequency hypothesis, of 1010 cm-3, which is typical of the chromosphere. Such a high density at the base of an open-field flux tube could only be found in a transient, according to conventional wisdom.

What are the implications here?

Once again, we are indebted to non-solar astronomers for pointing out a potentially large unexplored parameter space. The presence of very short time scales also implies very small spatial scales, and current-day numerical simulations of solar atmospheric structure do not address these scales. They are important because they come closer to the microphysics involved in solar plasma dynamics, and this chance observation should really encourage observers to tackle this parameter range.